How to Reduce Compliance Surface Area for CMMC Using Government-Furnished Equipment & Targeted Descoping Strategies

Why Compliance Surface Area (CSA) Matters for CMMC

When it comes to passing CMMC, the fastest way to readiness that secures your DoD contracts is not buying more tools or writing more policies.

It is deliberately shrinking your Compliance Surface Area (CSA).

Your Compliance Surface Area (CSA) is the total set of systems, people, and processes that fall within the boundary of your assessment scope. Think of it as the footprint the auditor sees when they ask: “What’s touching Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI)?”

The bigger your CSA, the more controls you need to prove, the more evidence you must generate, and the higher your costs and risks. In Department of Defense (DoD) contexts, where classified contracts and multi-tenant ecosystems collide, CSA can balloon almost overnight:

- Every laptop and endpoint that touches CUI.

- Every contractor or subcontractor with access.

- Every shared system that crosses the data boundary.

Unchecked CSA = higher audit costs, longer timelines, and more sleepless nights for CISOs and compliance leads.

For CMMC Level 1, only assets that process, store, or transmit Federal Contract Information (FCI) are in scope. Specialized Assets such as Government-Furnished Equipment (GFE), IoT devices, or OT are excluded. For Level 2, guidance is more complex: GFE is categorized as a Specialized Asset that must be documented in the System Security Plan (SSP), though it is not fully assessed beyond that documentation (see DoD CMMC Scoping Guide L1, DoD CMMC Scoping Guide L2).

The Risks of Broad CSA

A bloated CSA introduces measurable risks:

- Audit Overhead: Every new system in scope adds controls, documentation, and testing.

- People Risk: More employees in scope means more training, background checks, and insider threat exposure.

- Cost Spiral: You may need duplicate licenses, infrastructure, and monitoring tools.

- Timeline Creep: Preparing evidence across sprawling systems can add months to readiness.

Consider a hypothetical mid-sized defense subcontractor that allows employees to use personal laptops for CUI work. When assessment preparation began, every one of those endpoints fell into scope. Suddenly, they were on the hook to manage patching, logging, and access control for 400+ laptops, an impossible lift.

Or imagine a cleared integrator that stored project files on a shared corporate SharePoint. Because CUI wasn’t segregated, the entire corporate tenant fell in scope. Their CSA jumped from 30 users to 700 overnight.

Both scenarios show the same truth: failure to intentionally design scope can derail compliance readiness.

Descoping Strategies with GFE

The good news is that CSA isn’t fixed — you can design it. Organizations reduce CSA by making deliberate choices about how and where CUI flows. Four of the most effective strategies are below.

Government-Furnished Equipment (GFE)

GFE (laptops, phones, or endpoints issued by the DoD) can play a unique role in scoping. At Level 1, GFE is excluded as a Specialized Asset and not part of the assessment scope. At Level 2, GFE is treated as a Specialized Asset that must be documented in the SSP but generally is not tested beyond that documentation.

When in use, GFE is often managed under government baselines, with patching and hardening handled according to DoD standards. This can reduce the compliance burden on the contractor, though specific responsibilities vary by contract.

The tradeoff is reduced flexibility and occasional friction with corporate IT policies. Some contracts don’t authorize GFE use at all. But in clearance-driven environments, simplicity and auditability usually outweigh those downsides.

Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI)

Virtual Desktop Infrastructure creates a central enclave where all CUI is processed. Endpoints act as “dumb terminals,” streaming a secure desktop instead of storing data locally. Properly configured, this means only the VDI environment falls in scope, not the endpoints.

The CMMC Level 2 Scoping Guide notes:

“An endpoint hosting a VDI client configured to not allow any processing, storage, or transmission of CUI beyond the Keyboard/Video/Mouse sent to the VDI client is considered an Out-of-Scope Asset.”

For companies with remote staff or BYOD practices, this can drastically simplify compliance. The tradeoff is cost and performance. VDI licensing and infrastructure can be expensive, and if performance lags, employees will notice. Still, the burden of managing hundreds of endpoints is usually higher than the price of centralization.

Segmented VLANs

When VDI or GFE aren’t practical, network segmentation using Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs) is another option. A VLAN allows you to divide a larger physical network into smaller, isolated segments. Sensitive systems and users can be placed into a dedicated VLAN, separated from corporate IT.

By itself, a VLAN provides the logical segmentation, analogous to putting devices into separate “rooms.” Firewalls or Layer 3 devices then enforce rules about which VLANs can communicate. NIST guidance makes this explicit:

“Organizations should use firewalls wherever their internal networks and systems interface with external networks and systems, and where security requirements vary among their internal networks.” — NIST SP 800-41

This means that while VLANs provide the structural separation, firewalls are the enforcement mechanism that turns segmentation into a real compliance boundary.

This pairing helps organizations demonstrate to auditors that their CUI systems are segregated from corporate IT traffic. VLANs define the lanes, and firewalls decide which lanes can interact, preventing scope creep while aligning with NIST and CMMC expectations.

In practice, VLANs make compliance easier by giving auditors a clear boundary: they can see which network enclaves are designed for CUI and which are not.

VPNs and Zero Trust

Modern VPNs and Zero Trust frameworks reinforce scoping boundaries by strictly controlling identity and device posture.

-

VPN (Virtual Private Network): Traditionally used to create an encrypted tunnel between a user and the CUI environment. While VPNs are still widely deployed, relying solely on “being inside the VPN” is no longer sufficient for security.

-

Zero Trust: NIST SP 800-207 emphasizes that no part of the enterprise network should be treated as an implicit trust zone. Every access request must be authenticated, authorized, and continuously validated, with encryption applied throughout. Under this model, users and devices are assumed untrusted until verified.

For CMMC, these practices don’t automatically take systems out of scope. Instead, they strengthen the boundaries of the Compliance Surface Area by preventing unauthorized or unmanaged devices from drifting into CUI systems. Contractors that pair VPN access with Zero Trust principles (strong identity, device posture checks, least privilege) demonstrate clear alignment with federal best practices for protecting sensitive data in transit and controlling access.

Decision Framework

| Situation | Best Strategy | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Gov’t issues devices | GFE | Simplest scoping: no corporate assets in play |

| Remote/distributed workforce, BYOD common | VDI | Contain CUI in a central enclave |

| On-prem infrastructure, no VDI budget | VLANs | Segment workloads based on sensitivity (NIST best practice) |

| Highly mobile workforce, many contractors | Zero Trust (VPN + device posture) | Identity-driven access aligned with NIST SP 800-207 |

How CSA Shapes the Compliance Burden

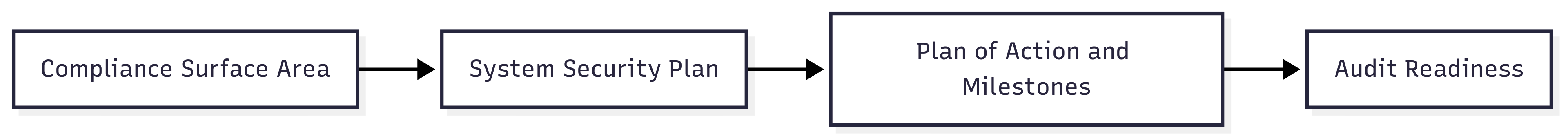

CSA is the first step that defines the weight of your compliance program. Every decision you make about scope ripples downstream into how heavy your workload will be.

Your System Security Plan (SSP) is the master blueprint of your security controls. It’s where you document how you meet each requirement. A large CSA means the SSP has to cover every system and user, sometimes hundreds of endpoints. A smaller CSA means you only need to describe a fraction of that.

From there, every gap identified in the SSP flows into the Plan of Action and Milestones (POAM), which is the backlog of remediation tasks. If your CSA is broad, you may generate dozens of POAM entries. If it’s tightly scoped, you may only have a handful.

Put simply: The smaller your CSA, the shorter your SSP, the lighter your POAM backlog, and the faster your audit readiness.

The Opsfolio Advantage

At Opsfolio, we’ve built our Compliance-as-a-Service (CaaS) platform to combine AI-enabled tooling with expert human guidance. We help:

- Organizations map their current CSA.

- Plan and implement descoping strategies like GFE, VDI, or VLANs.

- Support continuous scope alignment as contracts and systems evolve.

Our value is in combining technology with compliance experts so organizations can reduce workload, prevent errors, and prepare confidently for audits.

Action Plan

- Start with GFE if possible. Migrating users to Government-Furnished Equipment immediately shrinks your CSA and reduces audit overhead. Document all GFE in your SSP so auditors see the boundary clearly.

- Adopt VDI for remote/BYOD users. If your workforce is distributed, centralize CUI in a Virtual Desktop Infrastructure so endpoints stay out of scope. Prioritize vendors with FedRAMP-authorized offerings.

- Implement Zero Trust everywhere. Design your environment so no device or user is trusted by default. Enforce identity verification, device posture checks, and least privilege across all access paths.

- Use VLANs with firewalls and VPNs together. VLANs and firewalls create strong internal boundaries, while VPNs encrypt traffic in transit. Together, they give auditors clear proof of separation and control.

- Get expert help early. Partner with compliance engineers who combine automation with guidance. This prevents CSA creep, keeps SSP and POAM manageable, and accelerates audit readiness.

👉 Ready to see your CSA in action and protect your DoD contracts in the process?

Take our free CMMC Self-Assessment to identify your current in-scope CMMC readiness.